The Supreme Court of Iceland

The Supreme Court of Iceland

The form of the Icelandic Supreme Court building is a response to the surrounding buildings and the pressures of the enclosed spaces. The southern half of the site is reserved for a new sheltered garden.

The façades are predominately clad in copper sheet set upon a hewn basalt plinth. The public entrance in the south western corner is demarcated by a sawn basalt and other points of emphasis are denoted by honed metamorphic gabbro.

Public circulation is by means of a slowly ascending walk which allows the variously sized court and function rooms to be located according the their respective scale. An independent system is employed for the internal functions of the court.

The project for a new building for the Icelandic Supreme Court, was won in an open national competition in August 1993. The building permission was granted in November the same year and construction started in the autumn of 1994. The building was inaugurated on the 5th. September 1996.

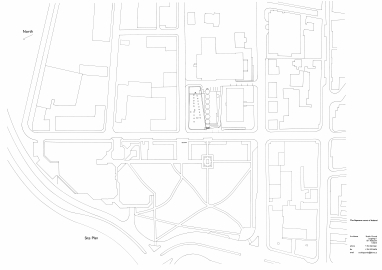

The site is on a low hill in the centre of Reykjavík between the State Ministries building, the former National Library and the National Theatre. To the west the hill is open to the Atlantic Ocean.

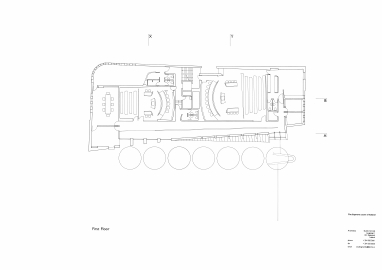

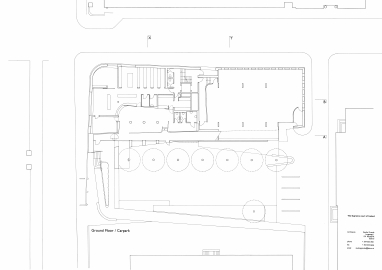

Lindargata, a chaotically disjointed street, defines the north boundary of the site. Occupying only the northern half of the site the building reinforces the street-line at the critical point when Lindargata opens to the sea. The southern part of the site is offered to the city as a sheltered garden, a precious resource in northern latitudes.

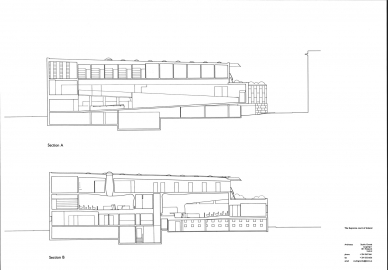

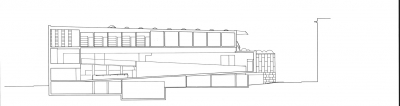

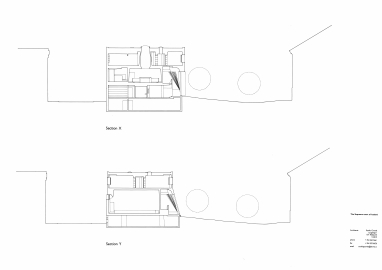

The building is highest and widest at its western end achieving a scale and proportion equivalent to the flanking Arnarhváll and library buildings. Towards the east the form is pulled and twisted both by the gravitational forces of the surrounding buildings and the pressures of the enclosed spaces so that it is gradually reduced in height and width towards the theatre. The eastern end is terminated by a lower, roof-planted block which overlooks a small square at the rear of the theatre.

The upper part of the street façades are clad in pre-patinated copper sheet above a hewn basalt plinth. On the south façade the copper is pulled from the from the building to meet the tilted grass plane of the garden. Slipping from beneath the protective green cloak a prismatic window hints at the circulation system within. The public entrance in the south western corner is demarcated by a sawn basalt clad tower and other points of emphasis are denoted by honed gabbró, an indigenous metamorphic stone.

The internal planning is primarily organised by the segregation of public and judiciary. The consequence of this division is two apparently complete buildings within a single enveloping skin.

From the low entrance lobby the public enter a long double-height space behind the south façade. From the ground floor reception a ramp runs the length of the building and back again at higher level. The court-rooms and reception rooms are arranged along the ramp and have diminishing volumes in relation to their scale. Daylight penetrates the space through narrow slots and at places of rest views are offered to the outside world.

Staff enter by the north entrance or via the naturally ventilated car-park. The internal functions are organised about a stair and lift core which culminates in the judges quarters on the top floor. The generous offices are served by a library, secretarial facilities and large meeting rooms for group working. The judges spend most of their time in these rooms which are exceptionally high and command long views over the ocean.

The courtrooms are embraced by the internal and public functions. The rooms share the same materials and finishes as the surrounding fabric but the volumes are more complex, fine tuned like a musical instrument to the precious value of the spoken word.

A limited pallet of oak, plaster, polished and fair-faced concrete and steel is used throughout the interiors with apparently simple details and conventional technology.

Built to close cost constraints the building was completed beneath the budget ceiling. This was achieved through design by maximising the volumetric use of the building and judicious specification of materials. However the quality of finish belies the economy of the project and this is largely due to the very close cooperation between the designers, contractors and client during all stages of construction.

.jpg)

_.jpg)

.jpg)

_.jpg)