Eastgate Theatre & Arts Centre

The reuse of disused churches is a familiar architectural project. In Peebles the Eastgate Centre has been placed in a nineteenth century whinstone church, listed Grade B for its townscape value.

The Client is unusual, being a collection of individuals associated with the many voluntary organizations in this town of population 11,000. The opening of the building has resulted from eight years of organization and fundraising with funds coming from the Scottish Arts Council, European Regional Funding, Local Enterprise Companies, but in particular, from a massive local fundraising campaign. Whilst supported by Borders Regional Council, the building is not a Council project, being wholly independent.

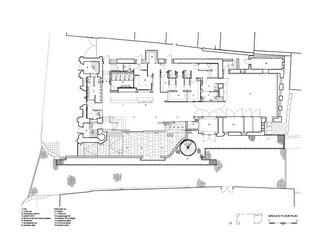

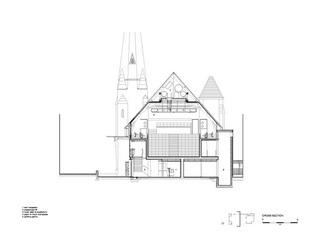

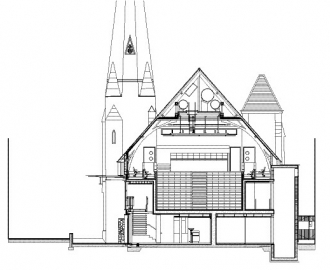

The building consists of foyer, café, artists changing, office and exhibition/performance space on the ground floor and a 240 seat flexible auditorium on the first floor. The majority of the seating is removable for flat floor events and it is envisaged that the Auditorium can be used for a variety of purposes: chamber music, professional touring theatre, films, local amateur productions and mass events such as the Christmas pantomime and on these latter occasions the secondary performance space can double up as a mass changing facility. The two floor solution was only made possible by excavating the ground floor and by providing a scissor lift for scenery to be moved up to stage level from the adjacent pavement.

Perhaps the most interesting architectural aspect of the conversion is the decision to locate the entrance not on the main street, using the original church door, but instead on a side street which connects The Eastgate (Peebless High Street) with the main carpark. The new façade of the theatre completely removed the entire side wall of the church. A giant beam holds up the roof and a new façade of steel, glass and timber reveals the foyer inside and the timber box of the auditorium above it as a building within a building. The stair and promenade to the auditorium is also clearly visible behind the façade. In summer the glazed screen to the foyer can be slid away so that the café occupies the new lowered section of the side street. A fire escape from the auditorium is expressed as an almost free standing Parisian poster bollard on the pavement and this also divides the façade into front of house and backstage, there being no access elsewhere for scenery delivery.

The building, therefore, now has something of a deliberately schizophrenic character. From the front it remains a church, although the original doors have been replaced with a timber screen but with a slot window which gives a hint of the new activity within. The new façade, however, is completely unambiguous, expressing clearly the totally new use to which the original building has now been put.

Reusing redundant churches are familiar architectural projects.

Churches have an architecture which is unmistakably all their own, (in particular the Victorian Gothic) and the new use inside frequently struggles to express itself on the exterior. In this instance, a radical move was made to preserve the main front of the church, virtually unaltered, and instead to completely remove the side wall to reveal through a new largely glazed façade the innards of the new function.

We believe that this radical solution is unique and could set the agenda in future for how this type of building might be converted for other public uses. In addition, the architectural language employed has clearly juxtaposed new with old, so that both can be appreciated simultaneously.