House Van Hee

The work of Marie-José Van Hee aims at a re-assembly of the basic elements of architecture and illustrates its meticulous attention for the character and scale of transition spaces, for the interlocking of rooms and for the thresholds between inside and outside, between the private and the public sphere, between day and night zones.

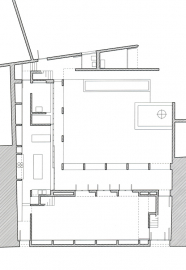

A good example of her approach is a courtyard house in an old quarter of the city of Ghent that Van Hee designed for herself. The house is built around an L-shaped gallery and a covered patio. In between the living spaces and the outside city garden are multiple larger and smaller mediating places. But also in between the public sphere of the street and the privacy of the domestic sphere a nuanced play of architectural elements is at stake: the high window in the front façade deprive every look towards the street, but nevertheless bring the roofs of the houses across even closer. The architecture of Marie-José Van Hee encompasses a sort of layering that is articulated with great but rudimentary detail, continuously arousing surprise.

On the street side, the house behaves scrupulously in the built urban context. The bricks have been given a light cement coating so that their pattern remains visible. There is no hard plastering to stress the building s newness, but a classic treatment of the façade, so that the house fits in almost invisibly without lapsing into formal associations. In contrast to the solidity of the surface of the façade, the edge of the roof has a fragile line. The façade s live high vertical windows already hint at the special interior concept.

The central space is a large, five-metre-high rectangular living room with a ceiling of wooden beams. The way daylight penetrates into this high space, with sunlight from morning to evening, evidences Van Hee s great mastery in making the orientation an essential part of the design. Architecture is used to make light visible. The large rectangular space evokes the image of the cleanly constructed rooms in aid rural Tuscan houses, spaces with an impressive brightness and exactly the right proportions.

A stone stairway leads to the library on the first floor, and next to it there is the bedroom. This bed room is connected to the garden by means of a covered outside stairway, which introduces a fascinating additional route. The large generous space, which does not separate the sitting room and dining room, incorporates a large table in the centre. By locating the table in this way, Van Hee dissociates herself from the stereotypical image of a cosy sitting area forming the care of the house. The kitchen and bath room are in the shortest arm of the L-shape. She deliberately relativises the concept of comfort in order to intensify the physical experience. In order not to escape the daily physical experience of the difference between interior and exterior, the toilet has even been placed outside.

A quest for authentic simplicity and austerity, connoted with a strong sensual element. She regards architecture as a medium in which slowness plays a part, and which enables us to go beyond the casual. She gives priority to seeking a timeless dimension. In order to rediscover the essential joys of life pursues sensuality in her work, rather than adopting a purist or ascetic attitude. She gives her buildings a new intensity, even a necessary sensuality. She seeks these experiences in all her buildings, and stands worlds apart from fashionable architectural tendencies.

Her own house developed slowly, over some seven years, taking time for any inessential parts to be removed so that what was already present from the outset would have time to develop. As Le Corbusier said when he spoke of travail patient , designing houses requires patient and intense work to penetrate to an essence, a labour far removed from the serial approach. Van Hee s private house is a genuine mirror of her way of living and thinking, an autobiographical house.

.jpg)

© David Grandorge

© David Grandorge

© David Grandorge

© David Grandorge

© David Grandorge

© David Grandorge

© David Grandorge

© David Grandorge