Tichel House

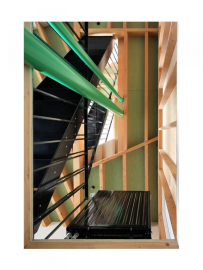

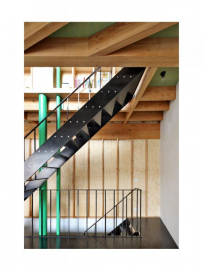

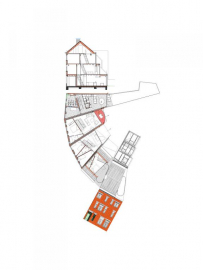

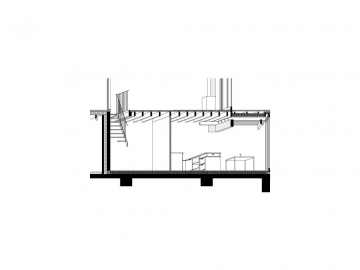

House T is one of four houses in a Kavel ensemble which have to deal with a bizarrely tapering site due to the adjacent party walls, reaching a point at the bottom of the garden. House T is at the right side of the ensemble. A rear wall which retreats on each successive storey and a roof disconnected from the party wall of the house on the right may form the most explicit implementation of designing in the section. This design lets the light penetrate everywhere, so turning the tapering plot shape to advantage.

The ambitions of AG SOB (Ghent Urban Development Corporation) go further than developing new urban districts and redrawing, in broad gestures, the existing urban fabric. Their Kavel project is an exercise in the precision implementation of small-scale housing following unconventional principles. The corporation seeks opportunities within the urban fabric arising if necessary through demolition to build new homes, either individually or in groups ranging from two or three to seven or eight. They do not manage everything themselves. Instead they offer the site to a young or otherwise suitable family, selected from a number of candidates, as a package complete with a selected architect, on highly advantageous terms. The deal is also bound by stringent conditions for financing and programme requirements: a high grade of sustainability is required on a practically impossible budget.

Four plots, or to be precise four families, declare themselves. Four houses are drawn. One of them is Tichelrei. At first sight four identical houses, but none of them is exactly the same. Not only are the plots different but the families too. Actually they may really be four different problem situations. Like any other assignment, they have nothing to do with one another. Or maybe they do.

One thing these houses have in common is that they were designed in section rather than in the plan. That is certainly the approach taken to each of these houses, as it was for many preliminary studies. It was not only the families that had to put in an application for these projects; so did the architects. The candidate architects first received an imaginary project to design. The exercise conformed to the real parameters of developing on inner city sites: narrow but deep, and of course multiple floors.

Another aspect that the houses share is the attempt to deal with the demands of the situation; but not just with the narrow, deep plan. Two of the four houses were faced with additional irregularities. In one case, the walls of the adjacent properties force the plot to taper practically to a point; in the other, the plot is so irregular that the house gains what could be described as a third facade.

Despite the impossible financial conditions, the house explores the margins of a certain brutalism, but with a certain precision in the same way as coal and diamond are chemically the same. Although sustainability (low energy consumption) is there, it is there in the way cement is in a brick wall: indispensible but scarcely telling a story. Sustainability is never a story. It is a form of economy as it should be, incontrovertible but not discussed.

The way the houses relate to the city. What living in the city is like. What living is like. Thats what it is about.

166 m²