Sport Hall and Square

One of the main focuses of Turato Architects Hall and Square project in Krk was to finish an architectural dialogue started back in 2005, when Idis Turato completed an elementary school, Fran Krsto Frankopan (with his former studio Randi? Turato).

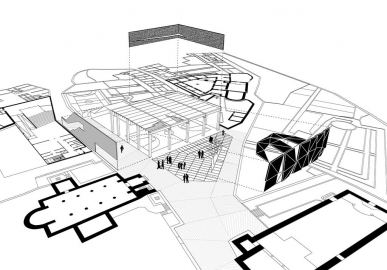

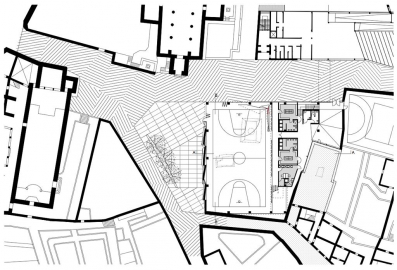

The new Hall is situated in the vicinity of the above-mentioned school, just across a narrow pedestrian street. The completion of the new sports building and public square was a crown achievement of the architects quest to complete an integral urban ensemble on top of Krks old town, thereby creating a newly defined focal point of high importance.

On the very site of the new Hall there used to be an old dorm, and prior to the Hall construction it had to be demolished. The demolition unearthed several important archaeological discoveries on the site, thus creating a whole new context for the Hall itself. All that had been found on the site had to be preserved as discovered. The architects took this fact to be crucial in redefining the concept according to the new input. This affected the very organizational scheme of the project. The excavated and preserved church and monastery walls were to become integral parts of the new building, with new walls and façades of the Hall emerging directly from the restored, older ones.

Yet another contextual element was important in forming the building; these high walls, seen throughout the old town of Krk, enclosing the town lots, lining the narrow streets of the town. The high walls of the western Hall façade, next to the Franciscan monastery, are a continuation of these town alleys. The story of the walls, their origin, context and shape began, resulting in variety of the façade walls, formally corresponding to the context, input and location.

Although seemingly set back on secondary surfaces the most recognizable and by far the most unique element of the Hall itself is a wall consisting of striking prefabricated concrete elements. The architect named these the innards due to their origin and fabrication, and the ambiguity of the impression they leave upon the viewer, due to a formal factor of its (un)attractiveness. The innards are in fact unique precast elements produced as a negative of a dry stone wall - made by placing stones in a wooden mold, covering them with a PVC foil and pouring concrete over it all. In this way the negative of the stones forms the face of the precast element. This inverse building process, a simple and basic fabrication with a distinct visual impact, is an invention of the Halls author. It happened as a result of researching simple building materials with a crafty bricklayer, with whom the architect had collaborated on several projects in the past.

The most representative façade of the Hall - one visually dominating the square, is constructed out of six impressively large concrete monoliths, weighing up to 23 tons. The monolithic blocks are finished off with a layer of terrazzo, which is an ancient technique usually used for floor finishes, requiring hours of polishing by hand. Here, however, the terrazzo is redefined and used vertically. While this sudden vertical use of the finish creates a shiny and finely shaded façade, its normal use, on horizontal surfaces, is recontextualized and rethought once again, since this finish, usually reserved for interiors, is now used for exterior surfaces of the public Square. The red color of the Squares terrazzo floor panels is in contrast to the lightness of the Halls façade. Size: 1020 m2 (square), 1312 m2 (hall)