Nationalmuseum

Sweden’s first and foremost art museum have reclaimed its architectural qualities that had been hidden for almost a century. This was possible by numerous innovative technical and architectural solutions that also introduced new features to the 19th century building.

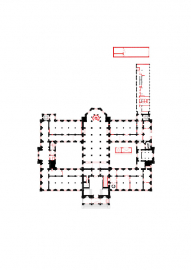

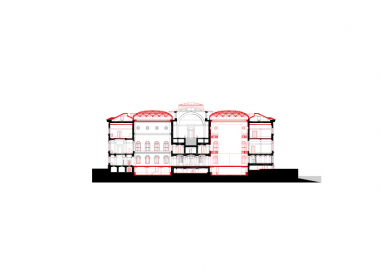

Nationalmuseum in the middle of Stockholm was built after the design of Friedrich August Stüler from Berlin and opened in 1866. A row of changes has been forced to the building since; In the 1910s a series of cabinets were replaced by a large hall, in the 1930s electricity closed almost every window and in the 1960s one of the two courtyards were destroyed and the central hall reduced in height. Contemporary requirements for indoor climate in museums also made large parts of the building unsuitable for paintings.

All technical systems have now been invisibly replaced, and the visitors are as originally intended able to enjoy the view of the environment and the interior in combination. The qualities of the 19th century as transparency, vistas and variation do once again meet the visitors. The lost courtyard is reconstructed and equipped with an acoustically inventive glass roof.

Visitors and artworks both now move along new circulation paths. The floor of the basement level has been lowered to make room for bathrooms and a coat check. These are reached by two new staircases, one of which is clad in the renovation’s characteristic finish: patinaed brass, a material with the ability to harmonize with the museum’s warm and soft character. Art and visitors alike can be transported in spacious elevators cladded in a veil of brass.

Raising the atrium floors made space below for large mechanical rooms and united the atriums with the building’s other public spaces. Together with the lowered Entrance Hall in the center of the building, they now form a grand, contiguous space.

In order to take advantage of the large windows without undermining the indoor climate or the lighting conditions, the later added interior windows were replaced with steel-framed glazing that together with solar shades can satisfy the complex demands for security, solar heat gain, views, daylighting, and insulation. Other examples of how earlier qualities have been reclaimed is the restoration of the upper-level floor plan and how air ducts and distributors have been applied.

The restoration applied the same materials originally used and the traditional crafts and skills wherever possible. This is visible in the floors, but also on the outside walls. Decayed stonework being replaced with the same type of stone as was originally used for the building.

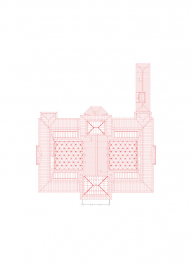

The glass roofs of the courtyards are innovations that deal with the fact that most courtyards covered with vaulted glass have terrible acoustics. These roofs are essentially domes too, each one consists of 104 triangles. Because each triangle is covered by a tetrahedron of glass, the roofs scatter the echo, primarily to the parts of the courtyards that are finished with a sound-absorbing acoustic render. The intricate geometrical pattern has decorative qualities that can rival the 19th century decoration of the museum, but was merely designed to make the echo disappear and the steel supports as slender as possible.

The new ceiling rosettes are another innovative feature in the project. They enable some of the biggest technical improvements of the renovation to remain almost invisible. Based on originals, new plaster rosettes were cast and fitted with sprinklers and ventilation diffusers.