Salamis - Summer House

Given a context of scarce resources this small summer residence reinterprets the space of leisure within a former site of production and labor. The postindustrial landscape of Salamis between city and nature, land and sea, informs the project’s introspection, which capitalizes on the essential resources of climate, outdoor space and economy of means.

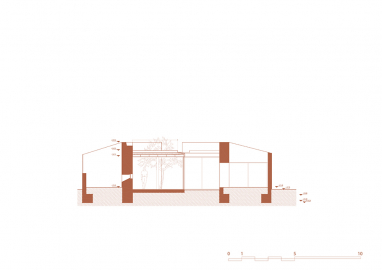

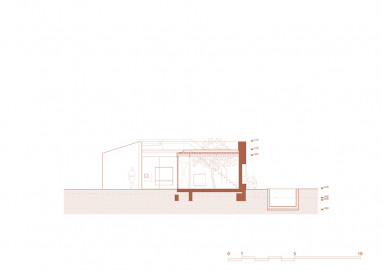

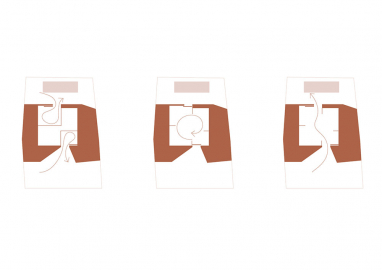

From the exterior, the solid walls appear as a monolithic construction, whose continuous surface of exterior insulation shields the contents of the house. They nevertheless conceal a large central courtyard within, accessed from the street by a tall gate. A second gate at the opposite end leads to a small garden and pool at the back of the plot. Within the main courtyard, two glass boxes divide the space into indoor and outdoor rooms, housing the main living areas. As the sliding glass doors are reconfigured, the house is split into two or unified around the central courtyard, according to the constantly shifting paradigm of outdoor living. Atop the steel construction, a small roof terrace reconnects visitors to views of the surrounding geography. Sleeping quarters occupy the two wings of the house, causing it to swell outward around secondary courtyards along the perimeter.

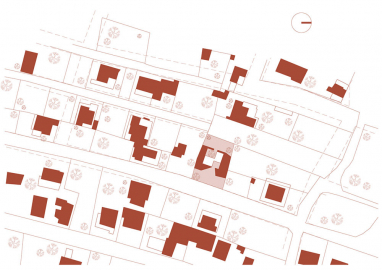

The island’s famous yet dying shipyards led to years of economic crisis and caused the surrounding settlement to develop informally, as an ad hoc mosaic of olive trees, man-made structures and tiny land plots separated by dirt roads, often dead ends. Scarce municipal infrastructures were implemented post facto, with no drainage network and with cables above ground. The indeterminacy of the settlement, but also the site’s small size, flatness and lack of external visual references, led to an inward-looking design strategy. The introversion anchors the house around the existing olive tree and well, creating small courtyards that benefit from the free resource of microclimate. While neighboring houses have formed through an additive process of makeshift extensions, here the house follows an inverse logic of subtraction, with voids removed from an initial volume. In some sense, the additive logic consumes the outdoors, while the subtractive logic produces it. But this is no longer the productive outdoors of the former olive grove; it now belongs to the space of leisure, released from the accumulated material needs of city life.

The four thick walls surrounding the central courtyard posses all of the necessary household fixtures within the niches bordering the kitchen and living room. Private rooms are embedded like cavities in the outer wings of the house, where additional small courtyards allow the light and air to infiltrate. A thin steel structure within the main courtyard opposes the heavy surrounding walls and reinforces the dual nature of the residence: fortified and porous, solid and transparent, monolithic and light. Surrounded by conventional concrete construction, brick infill with exterior insulation and colored plaster, the metal structure perhaps looks out of place on land, reminiscent of the types of construction used for ferry boats at the nearby dockyards. Painted with rust colored boat primer, it is a tribute to the maritime history of the island, to the shipyards and to the small ferries that connect Salamis to the mainland. As from a boat deck in the middle of an olive grove, after climbing the stair built into the wall of the courtyard, one gazes at the surrounding roofs, the mountain ranges and the sea beyond the olive grove.