The Cosmopolitan

The Cosmopolitan is not only a forerunner of urban renewal in a long-neglected area of Brussels. It also shows that an inventive strategy of targeted adjustments - both in-depth and on the surface - can give a new lease of life to buildings from the post-war building boom era and help improve the quality of life in a densely populated, diverse city.

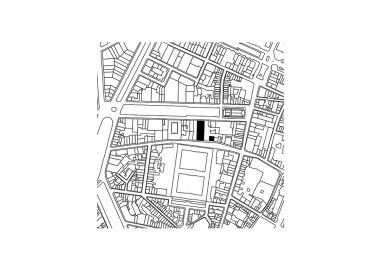

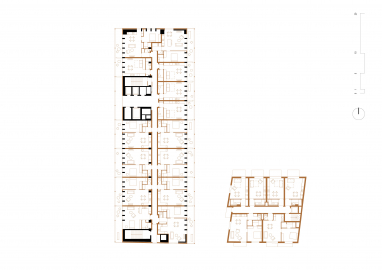

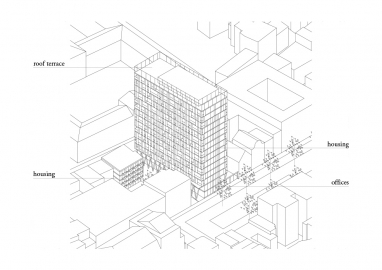

The ‘60s high-rise slab, standing perpendicular to the street, is an exception and a rare modernist insertion into the former Brussels’ trading port composed of late XIXth-century warehouses. Originally built as an office block, it suffered years of neglect. When the real estate developer Besix Red launched a competition for the building’s refurbishment, only the two lowest floors were used by a polyclinic. The proximity of Brussel’s Canal Zone and North railway station provided the impetus for redeveloping the building’s office spaces into 130 comfortable housing units ranging from compact studio flats to generous three-bedroom apartments higher up, with unique views to the east and west. At the south-east corner of the site, a new building with 26 dwellings was added to mark the volumetric transition between the high-rise and the neighbouring row of houses.

The design strategy is based on a critical review of the modernist insertion with no direct access to the street, as well as on an analysis of the potential of the existing load-bearing frame.

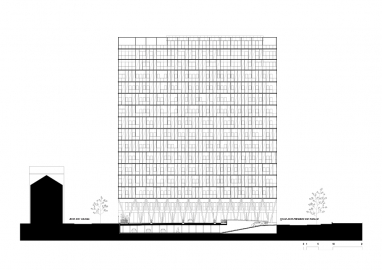

The existing grey façade was removed, exposing the concrete skeleton. Following a rigorous and precise reinforcement of the framework, the building was extended by adding three floors, which emphasises the slim silhouette. The preservation of the existing structure offers unique ceiling heights of more than three metres in all units.

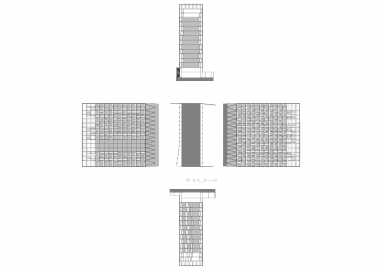

On the West and East façades, a new slice of generously sized balconies nestles in a lightweight steel structure, binding it all together from top to bottom. The double‑height access hall provides a visual extension to the exterior space. Two rows of double-height arcades running along the public lower floors give definition to the sheltered pedestrian path crossing the property. Consequently, the entrance of the building is brought to the street, anchoring the building in the urban fabric.

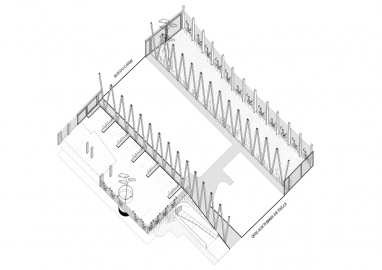

By placing varied dwellings in a structural network with dense façade pillars and even denser horizontal ribs, the structure defines the space. A secondary metal structure attaches to each of the two long façades. From the second floor on, the structure is composed of a grid containing individual balconies. White aluminium sliding panels, subtly perforated, serve as a protection against sun and wind, creating a permanent yet fluctuating play of light and shade that animates the façades and allows the building to become a landmark in Brussels’ skyline. The grids are supported, on the first two levels, by a colonnade of diagonal pillars.

Both buildings, old and new, are clad with large panels made of lightly polished white natural stone aggregate that enhance the elegant appearance of the ensemble. The underground parking connects both buildings and features 170 cycle parking spaces. The project relies on a soft mobility concept to go far beyond regulations and significantly reduce the number of parking spaces from more than 150 to 50. Above ground, trees and a variety of high grasses turn the semi-public areas into a welcoming and attractive urban area.