Rijksmuseum

Spanish architecture firm Cruz y Ortiz Arquitectos has spectacularly transformed the 19th-century building into a museum for the 21st century, with a bright and spacious entrance, a new Asian Pavilion and beautifully restored galleries.

The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam was designed in the late nineteenth century by Dutch architect Pieter Cuypers. The function of the building was twofold: one part was the national museum, the other the gateway to the south of Amsterdam.

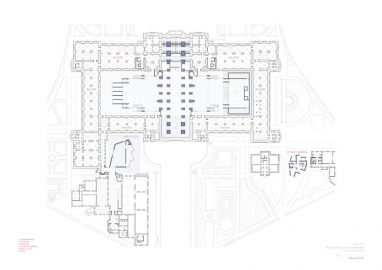

The museum use has paid an overly high price for its urban role as a connecting element between what was then the existing city to the North and the newer developments towards the South. A walkway - virtually a street - runs through the building from North to South splitting it in two parts, necessitating two entrances both towards the North and two main staircases; this means that only on the first floor are the Eastern and Western parts of the building are joined, while the ground floor and basement are divided.

The building has suffered many interventions over the last century: the need for exhibition space has meant building within the courtyards which led to a lack of natural light.

In summary, the museum suffered the usual lacks of museums of that period, i.e. a main hall unable to offer the proper capacity to the high number of visits and the need for essential services today such as information areas, shops, cafés, auditorium etc. In addition, the courtyards and galleries spaces lost their original size and shape.

The intervention on the building was, initially, meant to open up a new and unique entrance to the museum admission in the central passage hall, and secondly, to recover the courtyards and exhibition spaces, regaining somewhat their original state, or at least their dimensions.

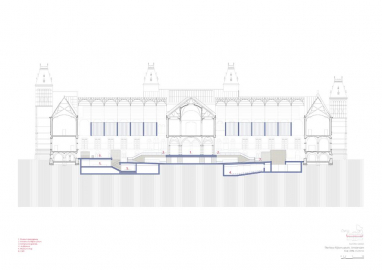

The first of these purposes could not be achieved due to the radical opposition of the cyclists, but it was possible to generate a large central hall to link the east and west courtyards of the building under the passage. The large space generated by opening and connecting courtyards houses all essential uses for visitors, and offers a suitable space on the scale that the grandeur of the building deserves. You enter this hall from the passageway, and the tours to the exhibition areas start at this point, linking with the original grand stairs.

In the new space created, natural limestone has been used as a basic material, a stone of a type not present in other areas of the building, but which allows us to unite the old and the new without complacency in the juxtaposition or contrast. This same material was used in the two new small interventions carried out in the garden. The courtyards, with a slightly sloping ground, are connected under the passage, and on each of them a structure with an acoustic and lighting mission has been suspended, the chandeliers.

The sustainable focus had to be found in doing justice to this monumental building with its non-alterable historic use and give it a thorough renovation with which it will follow up for another century.

The seasonal conditions are distinguished in summer and winter values, allowing the museum to be colder in the winter than in the summer, by which energy is saved. Then the applied insulation on the facades is a damp open system, which avoids accumulation of humidity in the exterior façade. The upgrade of the windows and glass in both facades as roofs have been improved within the boundary thickness of the original carpentries and the maximum allowed loads on the historic roof trusses.

Site: 30.000 m2 / Building: 30.000m2